Carbon trading threatens Indigenous peoples

The federal government admits that Canada is not on track to meet its official targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, Environment Canada says the gap between actual emissions and the goal of trimming emissions to 30 percent below their 2005 levels could be as much as 200 megatonnes by 2030 despite all the measures that Ottawa and the provinces have taken so far.

Little wonder then that Canada has not made a new submission to the UN climate secretariat with a more ambitious target than the one submitted by the Conservative government in May 2015. But there’s another aspect of the official Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) submitted by the previous government that has received less attention.

The INDC states that “Canada may use international mechanisms to achieve [its] targets.” Although the INDC does not state what portion of Canada’s emission reductions would come from purchases of credits from international carbon markets, analysts say Canada would have to buy a large quantity of offsets to meet its goal in the absence of other measures.

At the Paris climate conference Environment and Climate Change Minister Catherine McKenna mediated a contentious debate on carbon markets leading to their inclusion in Article Six of the Paris Agreement under the obscure name of “internationally transferred mitigation outcomes.” The article provides for a new international trading mechanism to replace the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) established under the Kyoto Protocol.

While Ottawa has not specified how many offsets might be purchased abroad, the experience with international carbon trading is alarming. The CDM has been plagued by widespread fraud, double counting and grave human rights violations.

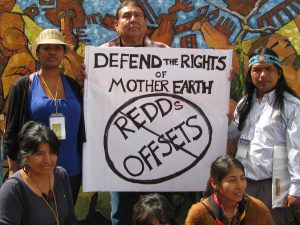

Indigenous peoples have strongly challenged the use of international markets for carbon credits. Offsets sold under the CDM and a similar scheme called REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) have frequently led to the displacement of Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories while putting lands and forests under the control of private companies. Too often complex ecosystems, supporting nature’s biodiversity, have been replaced by monoculture plantations. Water scarcities and air contamination due to the use of toxic chemicals have also ensued.

The Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP), representing peoples from 12 Asian countries, reports: “CDM projects implemented in Indigenous peoples’ territories have been disastrous for many communities, who have experienced land grabbing, displacement and food insecurity.”

The No REDD in Africa Network released a publication during the Paris conference which reported that violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights to free, prior and informed consent have occurred in 10 of 16 countries with UN REDD programs.

The International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change has reminded UN negotiators that “Indigenous traditional practices and livelihoods are not drivers of deforestation but rather contribute to mitigation and adaptation.”

In his encyclical Laudato Si’, On Care for our Common Home, Pope Francis warns: “The strategy of buying and selling ‘carbon credits’ can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases world-wide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require.”

As Ontario joins Quebec and California in a cap and trade system, its Climate Change Action Plan says the province will “look for opportunities to expand the carbon market throughout the Americas.” California’s offset program has been heavily criticized for allowing its industries to purchase offsets from projects in Brazil and Mexico without the free, prior and informed consent of the peoples affected.

If Canadian governments are serious about reaching an ambitious greenhouse gas reductions target, they would forego international carbon credits and set a minimum and rising national carbon fee starting at $30 per tonne of greenhouse gases at the wellhead or point of import; redirect subsidies away from fossil fuel and toward green enterprises and infrastructure; and offer low-interest loans for community and Indigenous initiatives, social enterprises, co-operatives renewable energy projects, and building retrofits.

By doing so, Canadian governments can close the gap between promises and reality when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, and the rights of Indigenous peoples.

John Dillon, Ecological Economy Program Coordinator KAIROS Canada

This op-ed was originally printed in The Hill Times, August 15, 2016.