Global Ecumenical Conference on Mining – 160 participants from 25 countries #KAIROS20

I grew up on the traditional and unceded territory of the Syilx Okanagan people in the province that was given the most colonial of all possible names: British Columbia. I am formed in settler notions of modernity that are “predicated on domination and colonization and cannot be understood unless viewed from the perspective of its underside.”1 And yet, in that place, while still in my teens, I found cues to set me on a meandering path to some of those perspectives, and to solidarity. For me, KAIROS is a big part of that journey.

It was through the work of local volunteers of a KAIROS predecessor coalition, Ten Days for World Development (as it was known in the 1970s), that I came to know about the work of Project North (another of the ecumenical coalitions, later called the Aboriginal Rights Coalition) with the Dene people in opposition to the oil pipeline that had been proposed for the Dehcho (Mackenzie River) valley. Through the Kelowna Ten Days group, we talked as well with leaders of Syilx people about their history, hopes and expectations. From those conversations, I learned that whatever we meant by “world development,” it had to include discussion of what was going on in our own neighbourhoods and across the bridge at the reserve.

Decades later, deeply into a sort of career that played out at the intersections of journalism, justice-seeking churches, and issues in Latin America, I found myself in a village in northern El Salvador.

A man sang a song that included this line: “If you love your cattle more than you love your neighbour, you cannot say that you love God.” And I thought about gold.2

This was in February 2011, three months before KAIROS would welcome 160 people from 25 countries to a global ecumenical conference on resource extraction—an event that still stands as a highlight of my collaboration with KAIROS and its predecessor coalitions.

When I heard that song, I was in a town called Santa Marta, located on the north edge of Cabañas department close to the Honduran border. In the 1980s, during El Salvador’s long civil war, the people had taken refuge in Honduras. That’s where they met staff from Canada’s Anglican and United Churches. In subsequent years, people from Santa Marta and nearby communities created a local development association (known as ADES), the community-led Radio Victoria station, a micro-credit program, and an AIDS education effort called CoCoSI. ADES and several of its related groups received funding from the United Church and from the Primate’s World Relief and Development Fund (PWRDF).

As the new century began, a new challenge emerged in Cabañas. In 2002, prospectors from a Canadian mining company, Pacific Rim, began looking for gold just north of the city of San Isidro. Eventually it was clear that they wanted to re-open a mine—El Dorado—that had been abandoned in the 1950s. By then, several years into my work as Latin America/Caribbean partnerships coordinator with The United Church of Canada, I was familiar with conflicts over resource extraction that affected partner organizations in a dozen or more countries from Argentina to Zambia.

Antonio Pacheco, the ADES executive director, first mentioned the mining issue to me in 2004 in a written response to a United Church survey of global partners regarding water issues.

“Before we knew about the damage caused by mines, we thought it was a good project because of the employment opportunities and development that it could bring,” Antonio explained later.3 “Our position changed when the people affected by Pacific Rim’s initial exploration came to our office to ask for help and accompaniment.”

ADES and its allies began to learn about mining in other countries, particularly Honduras, Peru, Chile, Bolivia, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. According to Antonio, over a period of two years, some 150 community leaders from Cabañas visited the Siria Valley in Honduras, which had borne the brunt of full-scale gold-metal mining.4 Some argue that the failure of another Canadian mining company to clean up adequately after its decade-long San Martin mining operation in the Siria Valley that provoked two decades of resistance to mining in Central America and beyond.5

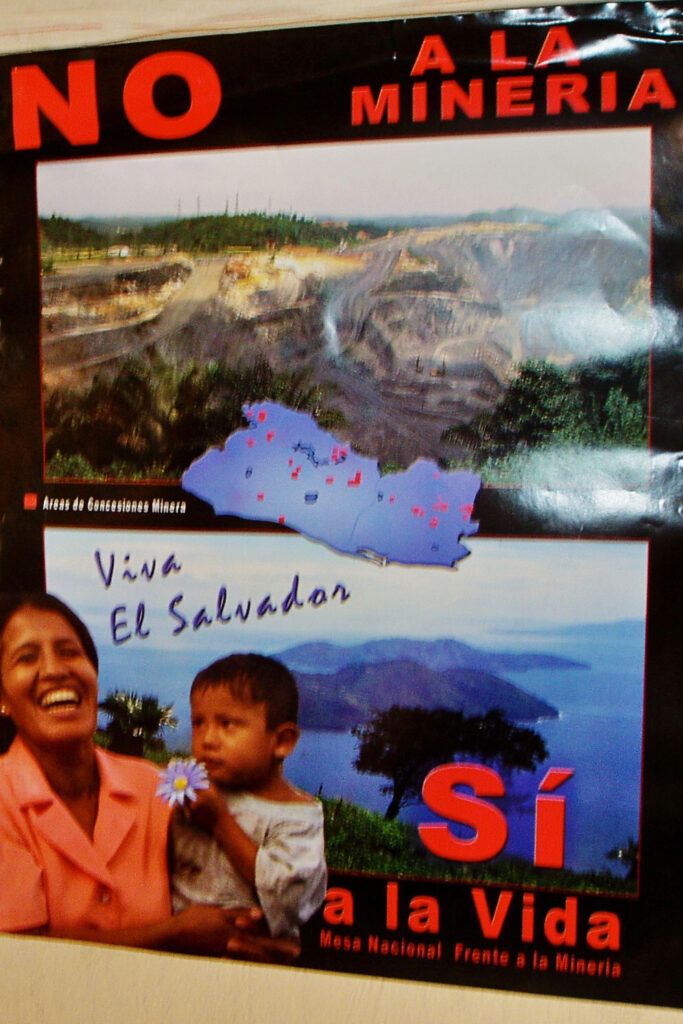

Just as it had done years earlier to ensure the success of its community development, health and education goals, ADES created local, national and global alliances to confront the Pacific Rim proposal. It worked with other community groups to create the Cabañas Environmental Committee. Since 2005, the National Roundtable on Metals Mining6 (known as “the Mesa” even in English) brought researchers, NGOs and churches together to seek a permanent ban on metals mining in El Salvador. In 2007, global supporters in the United States, Canada and Australia created a network called International Allies Against Mining in El Salvador.7

ADES and its allies contributed ecological, scientific and technical arguments to an environmental impact process that in 2008 led El Salvador’s Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) to say no to Pacific Rim’s request for an extraction permit. MARN agreed the mine would contaminate the rivers that flow into the Lempa River, a vital source of water for more than half of Salvadorans.

The government’s decision to deny the extraction permit sparked a furious reaction from people who might have benefited from the mine, particularly municipal officials linked to the conservative ARENA political party.

Vidalina Morales, an ADES board member who raised her five children in Santa Marta, was active in the Mesa and the international allies group. She would be among the participants in the Ecumenical Conference on Mining, held at the University of Toronto May 1-3, 2011.

“We began to receive threats and violence against our organization. They called us delinquents and said that we were against development,” Morales said later.8

In 2009, three community activists—Marcelo Rivera, Ramiro Rivera and Dora Sorto—were murdered because of their opposition to the mine. As Vidalina said, “Dora Sorto was 36 years old. She had six children and was eight months pregnant at the time. She was cruelly killed, just like the death squads that were used in the 1980s.” In 2011, Juan Francisco Durán, the son of another activist disappeared. Radio Victoria journalists, a local priest, and Antonio Pacheco were among those who received death threats.

In a world where cattle are more precious than neighbours, and gold more precious than water, it was the mining company’s next move that brought global attention to what had been largely an internal Salvadoran struggle.

Vancouver-based Pacific Rim moved a corporate subsidiary—Pac Rim Cayman, originally set up to avoid paying taxes on its future Salvadoran project—from the Cayman Islands to Nevada. In the wake of the government’s denial of the extraction permit, the company then used the “investor protection” provisions of the US-Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) and a Salvadoran investment law to launch a suit against El Salvador. The suit, filed in the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in Washington D.C., was launched on April 30, 2009. Initially, the company sought US$70 million from the Salvadoran government for lost future profits. This was later increased to $100 million and then to more than $300 million.

The suit took us into skirmishes that our KAIROS colleague and friend, John Dillon, had warned of decades earlier: so-called free trade agreements contained provisions that protected the interests of private corporations ahead of public health or ecology. Over the years, these suits became more common. John, who died in 2017, had spent most of his career working with the ecumenical coalitions: GATT-Fly (which became the Ecumenical Coalition for Economic Justice) and then KAIROS. He was a veteran of the 1988 debates over the original Canada-U.S. FTA, and then of the effort to build international alliances against the North American FTA in the early 90s and later the successful fight to defeat the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) in the early 2000s. His work informed our fight against the suit.

Details of this struggle in El Salvador are specific to that place and its social context. But rapid growth of Canadian mining operations in many parts of the world in the first years of the new millennium got the attention of church and other community leaders in places as far apart as Tanzania, Philippines and Guatemala. About 75 per cent of the world’s mining companies have their headquarters in Canada, and this country’s stock markets are where investors committed to resource extraction come to test their fortunes.

In Guatemala, conflicts between communities and companies in various parts of the country led a KAIROS partner, the Association for Community Development and Promotion (CEIBA), to organize community consultations9 based on the Indigenous right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) asserted in both the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (ILO 169, 1989) and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, 2007).

One of those conflicts played out in the department of San Marcos in the western highlands of Guatemala. There, a Maritimes-based network called Breaking The Silence (BTS) had developed relationships with the Indigenous Maya Mam and Sipakapense communities. When the mining issue emerged, BTS supported the communities.

So did the local Catholic bishop, Álvaro Ramazzini (named a cardinal by Pope Francis in 2019). At first, the communities and their allies tried to stop the mine with demonstrations, court challenges and political advocacy. But the Marlin Mine, operated by first by Glamis Gold and then by Goldcorp after the two companies merged, began production anyway.

Bishop Ramazzini was part of the planning process for the KAIROS mining conference and offered a keynote address at the event. Speaking of the communities’ struggle as it was still underway, he said:

“Goods should be shared through values of justice and charity, not just the rule of the law.” He added: “In the Mayan and the Christian cosmology, land, water, air are all gifts of God.”

CEIBA’s Naty Atz Sunuc was also among the speakers. “We say no to mining because we say yes to life.” She asked, “How do you restore a damaged ecosystem? The animals and biodiversity will never be the same!” (The Marlin Mine ceased operation in 2017, and the site is now controlled by a U.S. company, Newmont, but issues over clean-up and water quality persist.)

Another KAIROS partner, Ecuador’s Acción Ecológica, was represented by Gloria Chicaiza (whose death10 in 2019 saddened friends in Canada and around the world). “For a mining company,” she said, “a village, a community, a forest- all are in the way. You must get rid of them to mine.” Gloria’s work with other KAIROS partners and staff over many years would be key in developing the KAIROS emphasis on “gendered impacts” of resource extraction.

Conference poster

Pacific Rim mine site in 2010. Photo: Jim Hodgson

Post-it notes on mining

Drafters of the conference’s final declaration: Suzanne Rumsey, Primate’s World Relief and Development Fund; Jim Hodgson, United Church of Canada; and Moreblessing Chidaushe of Norwegian Church Aid in South Africa. Photo: Simon Chambers.

Vidalina Morales in 2006.

During the conference, I was struck by a difference between “educating” in the “Global North” and in the “Global South.” In the former, it’s about moving people of faith to act; in the latter, it’s about equipping affected communities to act.

There were differences of approach as well within Canada and across the continents. Some sought to wisdom about how to mitigate the worst effects of mining, while others sought ways to move beyond extraction-based economies. Some looked to “corporate engagement” as a mechanism to influence better behaviour, but others wanted the companies gone.

The final conference declaration11 noted “a crisis in the relationship between human beings and the environment.”

My own notes add: “Indigenous spirituality points to a way forward.” Indigenous speakers from territories within Canada said that First Nations peoples are sustained by two principles: a special relationship with the Creator, and a special relationship with the land. “We are one with the rocks, bush, tress, forest, clean water and clean air,” said Chief Stan Beardy of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation in northern Ontario.

The declaration continues: “First Nations speakers said that their communities feel the pressure of market demand for gold and other precious metals, and that legal protection for land rights is still inadequate. Canadians were challenged to consider the impacts of mining in Canada, where the consequences may be less visible but are no less damaging to the Earth and to many First Nations communities, and in other countries that are much more densely populated.”

The conference was intended to strengthen alliances across political and theological borders, and a decade later, the ways that many organizations confront mining issues reflect the awareness of the importance of partnerships. KAIROS includes mining justice12 in its work for ecological justice, the Women of Courage program, and Indigenous rights. KAIROS and its members work with other human rights and development organizations for Canadian standards for corporate behaviour overseas, access to Canadian courts for victims of abuse by Canadian companies, and for an effective, independent “watchdog”—an ombudsperson—with power to compel testimony and the production of documents from companies.13

Thinking again of those alliances and partnerships, let’s go back for a moment to Cabañas, where in 2011, the government of El Salvador and Pacific Rim were still engaged in that costly investor-protection lawsuit in Washington. By late 2012, the company seemed to be running out of money.14 Within a year, however, a much-larger Canadian-Australian company, OceanaGold, took over Pacific Rim and the risk to El Salvador became greater. But then the civil society alliances grew too, as opponents of OceanaGold actions in the Philippines, Australia and elsewhere joined the Salvadorans and their allies in a protracted struggle.

In the end, the people of Cabañas and their international allies won. In October 2016, that World Bank tribunal, ICSID, ruled for El Salvador and against OceanaGoldxv—an extraordinary victory in the long, unequal struggle for corporate accountability. And then, at the end of March 2017, El Salvador’s National Assembly approved a complete ban on all metal mining in the country, making it first country in the world to do so.15

Jim Hodgson retired in 2020 after 20 years as the United Church’s Latin America/Caribbean program coordinator. He had also served on the board of the former Inter-Church Coalition on Human Rights in Latin America, on various program committees of KAIROS and on its steering committee.

End notes

- Medina, Néstor. “A Decolonial Primer,” Toronto Journal of Theology 33, no. 2 (2017): pp.279-287. See: https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/tjt.2017-0149.

- Some parts of this article are drawn from articles I wrote for the United Church of Canada’s mission magazine, Mandate. See: “A Life-Long Passion,” Mandate, Feb. 2011, pp.16-17, and “David defeats Goliath,” Mandate, February 2017, p. 14.

- “Interview with Antonio Pacheco, Director of ADES,” http://voiceselsalvador.wordpress.com/2010/06/18/interview-with-antonio-pacheco-director-of-ades/. June 18, 2010.

- Leonard Morin, “El Salvador’s Misfortune in Gold: Mining, Murder, and Corporate Malfeasance, http://www.alterinfos.org/spip.php?article4368, April 21, 2010.

- Leonard Morin, “El Salvador’s Misfortune in Gold: Mining, Murder, and Corporate Malfeasance, http://www.alterinfos.org/spip.php?article4368, April 21, 2010.

- Leigh Anne Williams, “Salvadoran activist takes her case to Canada,” Anglican Journal, https://www.anglicanjournal.com/salvadoran-activist-takes-her-case-to-canada/, March 22, 2013.

- “Groundbreaking Study on Free, Prior and Informed Consent,” https://www.kairoscanada.org/now-available-groundbreaking-study-on-free-prior-and-informed-consent, Feb. 5, 2015.

- Rachel Warden, “Gloria Chicaiza, Presente!:” https://www.kairoscanada.org/gloria-chicaiza-presente, Jan. 8, 2020.

- “Ecumenical Conference on Mining – Final Statement:” https://www.kairoscanada.org/ecumenical-conference-on-mining-final-statement. May 5, 2011.

- “Remember the Land: Global Ecumenical Voices on Mining – Study Guide:” https://www.kairoscanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/SUS-RE-RememberTheLand_StudyGuide.pdf

- “We’re Still Waiting for an Independent Ombudsperson with Investigatory Powers:” https://www.kairoscanada.org/what-we-do/ecological-justice/open4justice.

- Robin Broad and John Cavanagh, “A Strategic Fight Against Corporate Rule,” The Nation, Feb. 3, 2014, pp. 21-25.

- Jen Moore, “El Salvador: OceanaGold must ‘pay up and pack up,’ Canadian Dimension, Winter 2017, Vol. 51, Issue 1, and https://miningwatch.ca/blog/2017/2/23/el-salvador-oceanagold-must-pay-and-pack.

- Aldo Orellana López and Thomas McDonagh, “The Anti-Mining Struggle in El Salvador – Corporate Strategies and Community Resistance:” https://miningwatch.ca/news/2017/7/31/anti-mining-struggle-el-salvador-corporate-strategies-and-community-resistance, July 31, 2017.