Will Canada listen to Indigenous peoples on carbon offsets?

In his speech to the Paris climate conference, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to work with “our provinces, territories and Indigenous leaders who are taking a leadership role on climate change.” For extra emphasis, he added: “Indigenous peoples have known for thousands of years how to care for our planet. The rest of us have a lot to learn.”

Following the Prime Minister’s lead, Canadian negotiators are advocating for the recognition of human and Indigenous rights in the final climate agreement.

If the Canadian government is serious about learning from Indigenous peoples on caring for Mother Earth, it will have to reconsider core aspects of the policies it inherited from previous administrations.

Given the short period between the federal election and the Paris conference, the prime minister reasonably maintained that he did not have time to revamp the greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets in Canada’s May 2015 submission to the UN climate secretariat. As a result, the former government’s submission, i.e., the Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC), remains Canada’s official position until a new one is issued. To her credit, Catherine McKenna, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, has said that the goal of cutting GHG emissions to 30 per cent below their 2005 levels by 2030 will be a floor on which Canada will build a more ambitious commitment.

There is another aspect of Canada’s INDC that also must be revised if it is to respect the views of many Indigenous people. It states that “Canada may use international mechanisms to achieve [its] target.” Analysts conclude that Canada would have to purchase a large quantity of carbon credits from abroad just to meet what the new government acknowledges are inadequate targets.

Indigenous peoples have strongly challenged the use of international markets for carbon credits that turn nature’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide into a commodity to be bought and sold. They see international carbon trading as a false solution to climate change, one that has too often violated Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Tom Goldtooth, Executive Director of the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) believes the UN climate negotiations, dominated by industrialized countries and their corporations, create a power structure that:

“minimizes the importance of Indigenous cosmologies, philosophies and world views. [It operates from] an economic system that objectifies, commodifies, privatizes and puts a monetary value on land, water, air, forests, plants and practically all life. This is contrary to Indigenous thought. The subordination of the Web of Life to the chains of the markets and growth of the corporate-led system erodes the primary means of existence on this planet, which is rooted in the diversity of life itself.”

He goes on to say:

“Carbon trading, offsets and other market-based systems…turn the sacredness of our Mother Earth’s carbon-cycling capacity into property to be bought or sold in a global market…. Carbon trading will not contribute to achieving protection of the Earth’s climate. It is a false solution with many risks, including the dangers of entrenching and magnifying social inequalities and human rights abuses. From the Indigenous mindset, it is a violation of the sacred, plain and simple.”

Goldtooth’s critique is grounded in the experience of many Indigenous peoples under two carbon trading mechanisms: the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), attached to the 1997 Kyoto protocol, and the UN program for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). In theory, both reward developing countries, and communities within them, for actions that reduce GHG emissions or capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through, for example, planting forests.

In practice, however, the CDM and REDD projects have frequently displaced Indigenous peoples from their traditional territories while putting lands and forests under the control of private companies. Too often complex ecosystems, supporting nature’s biodiversity, have been replaced by monoculture plantations growing eucalyptus or oil palm, usually for export. Water scarcities and air contamination due to the use of toxic chemicals have also ensued.

The International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC), noting that some 60 million people worldwide depend on forests for their survival, has warned: “REDD will steal our land. States and carbon traders will take control over our forests.” The IIPFCC reminds UN negotiators that “Indigenous traditional practices and livelihoods are not drivers of deforestation but rather contribute to mitigation and adaptation.”

The Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact (AIPP), representing peoples from 12 Asian countries, report: “CDM projects implemented in Indigenous peoples’ territories have been disastrous for many communities, who have experienced land grabbing, displacement and food insecurity.”

For example, Karen villagers in Thailand were convicted of illegal possession of timber, clearing forest land and “obstructing official business” because their activities were at variance with the government’s new Forestry Master Plan. In reality the Karen people were only cutting wood for building and maintaining their houses.

Indigenous leaders insist that land use and forestry preservation plans must not proceed without consultation and the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the peoples affected, as required by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. They insist that Indigenous peoples are in the best position to take care of their own lands based on their own cultural and spiritual traditions. A new publication released in Paris on December 7 by the No REDD in Africa Network reports that violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights to free, prior and informed consent have occurred in 10 of 16 countries with UN REDD programs.

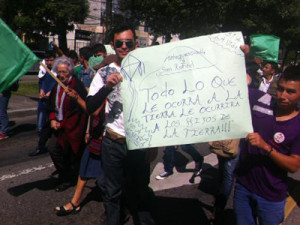

On Sunday, December 6, a colourful flotilla of kayaks and canoes paddled by Indigenous peoples from the Arctic to the Amazon took to the Seine river in Paris demanding holistic solutions to climate change to protect Mother Earth. At that event, Dallas Goldtooth, an organizer with the IEN, declared: “Carbon trading and REDD projects are schemes to continue business-as-usual, nothing more. We, as frontline Indigenous communities, are the arbiters and innovators of real solutions towards mitigating climate change.”

Yet the negotiating draft for a Paris agreement tabled on December 9 contains articles that would make carbon markets part of the final deal. Pablo Solon, former chief negotiator for Bolivia, notes how a newly introduced clause with the innocuous title of a Mechanism to Support Sustainable Development would re-incorporate the Clean Development Mechanism into the Paris agreement. This initiative ignores a report from the CDM’s executive board explaining that it has had to reduce its program by one-third due to low demand and low prices for the carbon credits it administers.

Similarly, the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) has been plagued by low prices with up to two-thirds of the credits issued during its first seven years of operation having failed to achieve real emission reductions. Undeterred by these failures, business groups in Paris are lobbying for a framework that would link 55 existing emissions trading schemes into one global market. (Financial Times, Dec. 7, 2015, “COP21: Business seeks global carbon pricing at climate summit.”)

At the request of French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius, Environment Minister McKenna has been tasked with mediating between those countries that want references to carbon markets removed from the agreement and those who want them retained. She told The Globe and Mail that “whether or not the language [of markets] is reflected in the agreement, there will continue to be a role for the markets.”

In his encyclical Laudato Si’, On Care for our Common Home, Pope Francis reminds us that we have much to learn from Indigenous peoples who have “a greater sense of responsibility, a strong sense of community, a readiness to protect others, a spirit of creativity, [and] a deep love for the land.”

The Pope also warns:

“The strategy of buying and selling ‘carbon credits’ can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases world-wide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require. Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors.”

In KAIROS Briefing Paper #42 Canada Falls Far Short of Pope Francis’ Call for Ecological Justice, we describe how international carbon trading schemes have been tarnished by fraud, speculation and human rights abuses while failing to achieve meaningful GHG reductions. Offsets, by their very nature, do not diminish overall emissions as they allow pollution to continue in the North on the promise that it will be reduced in the South by a similar amount.

The federal government and the provinces must decide whether they will resort to buying credits on international carbon markets to make up for shortfalls in domestic GHG reduction measures. As Ontario and Manitoba prepare to join the trading scheme already operated by Quebec and California, they must consider carefully whether they will allow carbon credits to be purchased from abroad. California’s offset program has been heavily criticized for allowing its industries to purchase offsets from projects in Brazil and Mexico without the free, prior and informed consent of the peoples affected.

John Dillon is the KAIROS Ecological Economy Program Coordinator.

Photo: Allan Lissner, Indigenous Environemental Network