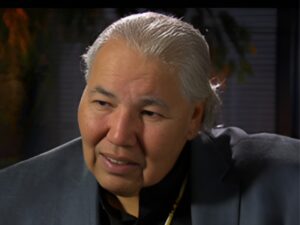

How Residential School has affected me: a reflection by Sui-Taa-Kii (Danielle Black)

Sui-Taa-Kii (Danielle Black) is from the Siksika First Nations, which is a part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Plains people, Treaty 7, and delivered this speech at a recent gathering “Abiding in Right Relations: Laying the Foundations”, a cross border conversation following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

A few weeks ago, my grandparents approached me to speak about my experiences with Residential Schools, and how it’s ultimately affected me and my life. My first thought was “YES! there’s no question, I have to do this.” but I didn’t realize the amount of self-reflection, and looking back in retrospect I would be doing. Every day when I walk down the street, I am aware of the color of my skin, I am conscious of how others may perceive me based on my background, and the older I get, I understand how conditioned and habituated I am, we are, to the oppression we face. The ultimate question being asked today is, “how has Residential School affected me,” and I can safely say that it has left its intergenerational impacts on all of us. It did not only affect the survivors of these institutions, but it will affect the lives of our people for years. It has deeply affected me, and will continue to unfold and do so for the rest of my life.

In my culture, it is a traditional practice to tell a story through word of mouth. We listen to stories to entertain us, to make us laugh…. cry, but we used them to teach and to educate. I wanted to thank everyone who is here, who is willing to listen. Every one of us has a story to tell, and for native people, we have a unique one. This is an important topic, and our voices need to be heard. I am happy to be given the opportunity to share my experiences, and my hopes here today. Today I wear my heart on my sleeve, and fight for my people by telling some of my story.

My name is Danielle Black, and my family is from the Siksika First Nations which is a part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Plains people, Treaty 7. My native name is Sui-Taa-Kii, which means “Rain woman.” It was a name given to me from my Grandparents. I keep this close to my heart. One, because it is a name I share with my great Grandmother, who was a strong Cree woman, but it has also gifted me a connection to everything that roots me, my culture, my heritage. Rain woman, Sui-Taa-kii, its music to my modernized, reconditioned, and some might say my colonized ears. I grew up in the city, far away from a lifestyle that my people used to live. Anything that allows me to have a connection with my ancestors, how can I not be filled with honour? When my grandparents call me by that name I feel proud, and I feel immensely happy. On the other hand, I am also reminded of how lucky I am to hear my native language, reminded of how close we were to losing something irreplaceable.

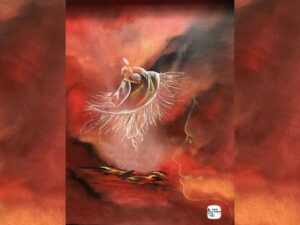

As a Blackfoot, my people have always been seen as fiercely strong warriors. I remember as a child, being mesmerized by the paintings that covered my grandparent’s walls of men and women painted brightly. Warriors, chiefs, strong women and they emitted strength, courage, and power. It was impactful. We are strong people. Although I do not fight the same battles as they once did, my people still face conflict and wars that are continually being fought, lost and won every single day. Back then, my ancestors fought for their lands, against colonization, they fought so they could continue to live how they were meant to live. Today, we fight against a society that looks down on First Nation peoples, with a government that looks at our women as less worthy to care enough that more than 1,200 of our women have gone missing and murdered, and more continue to go missing and are murdered every single day. Most importantly, we have fought against and live in a country that’s past involved the striping of aboriginal people, more specifically children, of their language, their culture, and their families. Killing the Indian in the child. Everything that made us who we are, all of it was taken away. My grandfather and grandmother attended one of these schools.

I have a strong mother. I look at her, and I’m proud to be her blood. She built us a life in Calgary, she worked hard for what she has, and she gave her child the opportunity to have the world at my fingertips. I am thankful because everything that I have, everything I keep close to my heart, my life, is because of her. My mother is what courage looks like to me. My mother is the daughter of my Grandparents. She is strong, because they are strong. They are powerful, they are resilient, they are survivors. If they weren’t fighters, I wouldn’t be here. I honor them.

I’m sorry they cut your hair, I’m sorry for the pain they caused, I’m sorry they deprived you of your language and your culture. I’m sorry they told you that everything about you was wrong, and that you needed to change. I honor the children that never made it back home, and the stories they took with them. I honor the parents who watched their children being taken away. I am heavy, and I will not talk about this without recognizing the pain that has been caused to my people.

How has Residential School affected me? Big questions get big answers. For the majority of my life, I grew up in the city. My experience is very different compared to someone who has lived on the reserve, and I acknowledge that. When I was young, I lived with my grandparents on the Piikani First Nations reserve. I remember travelling around southern Alberta with my grandparents. Driving along dirt roads, passing all the deteriorating signs and buildings, and watching the stray dogs chase our car. I remember long braids, the wrinkles on the elders hand’s and faces; I remember the colourful and vibrant pow wows, the drums, the chants. I remember wanting so badly to become a fancy dancer, there was nothing more beautiful to me. I would look around and see the same strong men and woman that I would see in the paintings on the walls. I was the Indian girl who was capable of anything. When I moved to the city, things were different.

I am 22 years old, and I live in Canada. In the school system, we are taught Canada’s history. However, one thing that was never taught to me was the implementation and practice of the assimilation of Indigenous people through Residential Schools. I was failed by the school system on educating me, and others, on a massive section of Canadian history. I went to a school that was named after, Langevin, who believed in civilizing the Indian and helped curate these schools. I grew up in a society that looked down on native people. I would constantly hear the lack of respect people had towards us. The little native girl who was capable of anything started to believe that because I was native, I was lesser. How do I change that? By adopting a new form, and disowning my heritage. I lived my life pretending I was not First Nations. I pretended to be white, so I would be accepted by others. My people are survivors, they survived the big things, but it’s the little things that hurt the most. I have stories of racism growing up. It was going to a Chinese restaurant in Fort Macleod, and noticing that my family and other native people being blatantly segregated from the non-natives in the restaurant. It’s the comments I would receive from people saying, ‘Oh you don’t look or act native, how nice, good for you.” It was hearing about the jokes about drinking Listerine, and that we are all a bunch of drunks, and that we deserve what’s happening to us because it’s our fault for what’s happening. It was standing in a room full of people, and having someone yell out, “Who hates native people?” and having everyone put their hands up while I stood there, but everyone laughing and sarcastically saying sorry to me but knowing I was “white washed” enough to not be affected,. Maybe at the time I had agreed to all those accusations because everything that surrounded me told me that what I was was bad, that my people were bad. I was left questioning my identity, and it led to self-abusive behaviors. I looked at myself like I wasn’t worthy, that because I was native, I should hate that part of me, and I did. That lasted through most of my teenage years. My partner at the time was half Blackfoot, but his grandma went to Residential School, and lived on a reserve a good portion of her life. She passed away a few years ago, but I also heard stories of the many children she brought into this world and took care of them. She was strong woman, but her perspective saddened me. I remember when we would be at their family gatherings the topic of my background would come up. They would bring up the fact that I was native. “Aaron is the only one dating an Indian.” And I would sit there and smile, but the reason it was talked about was because their grandma always told them not to date a native person. It wasn’t that she hated her people, but she had a fear that her family would be brought back to the reserve, and all her hard work of getting out of there would be for nothing. I would look at this family, and her influence was there. It’s sad, and heartbreaking a grandmother has to think that way. We are a product of our past, we are a product of our environments, but we don’t have to be prisoners of it.

Today, I am a very different person. I was a part of an aboriginal upgrading program, where I met several people from different reserves trying to make a difference in their lives. That’s where I learned how to smudge and cleanse myself. We sat at the feet of our elders. We laughed together, and we cried together. I would like to mention a girl named Christy, who went to this school with me. She had two kids, and had stories of her own experiences as a native person, but she was there to change her life. Recently she was found, beaten to death by her boyfriend at a party. She left behind her two children; they no longer have a mother. She was trying to make a better life for them. In the media, they covered her death, but thought it was okay to mention how this was an “Indigenous party.” Our stigma is still there. Stories like this happen every day. Our people are in a crisis. We live on reserves that are in Third World conditions, we are continuing to lose our language and the people who carry that knowledge, and we are losing our brother and sisters to violence, drug and alcohol abuse, and acts of hate. I want to change that. As much as I have looked back, I have also been given the opportunity to look forward. I have gone to sacred circle, and met incredible Indigenous people that I keep close to my heart. I’ve heard stories. Some tragic, and some heartbreaking, but some that give me hope for a better life for us. I want to help change the way people look at aboriginal people, and I want us to change the way we look at ourselves. I want our missing and murdered sisters to be found, and come home. I want our lands to be respected, but until then, my people will continue to fight, and I will be there alongside them. I will raise my fist in the face of my oppressors, and show my ancestors that we are still warriors, and show those children who were hurt that I, WE, fight for them.

But most importantly, I want us to heal. It will take us generations, but I can feel the path begin to open, I can feel the connections start to bond again. Like many others, I am waking up, and staying “woke”. *

* “Woke” – a term the black community uses to acknowledge their oppression and oppressors. They have equipped themselves with the education on what has happened, and what is happening to them through history and present day.

Photo by Elizabeth S Cameron: Danielle Black in the boiler room of the Old Sun Residential School in Siksika.