Ontario mustn’t backslide on education about Indigenous issues

It was déjà vû. When the Ontario government cancelled curriculum-writing sessions this summer on truth and reconciliation, I was immediately taken back to 1998 when I was part of a team writing curriculum for the Ontario Ministry of Education.

At that time, I was working on Indigenous-focused curriculum in secondary courses on the arts, history and geography. The provincial government promised that this curriculum, developed primarily by Indigenous educators, would be mandatory for all schools in the province. However, and despite assurances, at the 11th hour “mandatory” was replaced with “recommended” – against our wishes.

I am an Indigenous teacher who grew up learning little about Indigenous peoples in Canada. Growing up, I suffered through discriminatory comments sneered in whispers from the back of classrooms. I was called a “dirty squaw” and often felt alone. I knew that providing teachers and students with a more inclusive curriculum would have helped dispel stereotypes, while engaging us in the possibility of healthy discussions.

But with this reversal, the spirit of renewal and improved education cited in the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, which was published just two years earlier, was denied to Ontarians.

The result: Very few Ontario schools offered courses with Indigenous-focused curriculum. Money wasn’t allocated to hire Indigenous teachers or train non-Indigenous teachers. Administrators weren’t exposed to the win-win-win outcomes of having more inclusive and accurate curriculum, and so there was no incentive to buy in to the new courses. A generation of students lost an opportunity to learn Canada’s history with Indigenous contributions and insights.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) issued 94 “Calls to Action” for all Canadians, based on painful testimony from residential school survivors. For more than a century, until 1996, Indigenous children in Canada from the ages of four to 16 were taken from their homes and communities and placed in residential schools – which were more “institution” than “school.” The vast majority of the 150,000 children who attended these schools experienced neglect and abuse.

In its summary report, the TRC attributes “the current state of troubled relations” between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada to “educational institutions and what they have taught, or failed to teach, over many generations.”

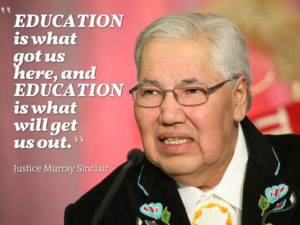

In the words of TRC Commissioner Sen. Murray Sinclair, “education is the key to reconciliation.” He adds, “Education got us into this mess, and education will get us out of this mess.” Education is the cornerstone for change, starting on the playground. Vincent Solomon, a former employee of the St. James Assiniboia School Division in Manitoba, recently explained that when Indigenous perspectives were brought into classrooms, there was a marked decrease in racist incidents among children at the school.

In Call to Action 62.i, the TRC urges provincial and territorial governments to ensure that the residential schools, treaties and the historic and contemporary contributions of Indigenous peoples are taught from kindergarten to Grade 12.

It is imperative that Indigenous peoples be included at all levels of the planning and implementation of this call. “Nothing about us, without us” remains as relevant as ever.

Since the release of the TRC’s Calls, KAIROS Canada has graded Canadian provinces and territories on their public commitment to and implementation of Call to Action 62.i, including their consultation with Indigenous communities.

In KAIROS’s updated Education for Reconciliation Report Card, released on Oct. 9, most provinces and territories are making progress on Call to Action 62.i. Ontario has made significant improvements since 2015 in its commitment to and implementation of this call. In 2017, the government, in collaboration with residential school survivors and Indigenous partners, revised this fall’s social studies and history curriculum from grades 1 to 10 to include treaties, residential schools and Indigenous achievements. But there is still a lot of work ahead of us.

The new government in Ontario has made a public commitment to continue with the updated curriculum. However, in the summer of 2018 it cancelled planned meetings with Indigenous educators to continue this work and has not re-scheduled them.

This province cannot afford to reverse efforts on reconciliation through education. We owe it to the next generation to fully implement Call to Action 62.i . It is within Ontario’s reach.

Originally published on October 25, 2018, in the Ottawa Citizen.

Dawn Maracle, Indigenous Rights coordinator for KAIROS Canada, is a Mohawk from Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory. For close to 25 years she has worked with Indigenous and non-Indigenous organizations and communities in Canada and internationally on issues related to Indigenous education, activism, women’s rights, health and governance.