Fort Chipewyan: Time for Treaty Renewal

In so many ways, Fort Chipewyan’s story mirrors that of Canada. Its rich history includes Indigenous peoples, explorers, fur traders, disease, corporations, governments, treaties, residential schools, and the church. In the late 1700s, Fort Chip – as the locals call it – was at the centre of a global economy that shaped an emerging nation state. Today, it is at the centre of the issues that will define Canada’s future. Back then it was furs. Today it is oil. For the people of Fort Chip this is nothing new; it’s the latest chapter in a long and complex history of relationships – nation-to-nation, people-environment, European-Indigenous, economy-ecology.

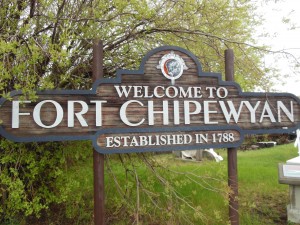

On the shore of Lake Athabasca, Fort Chip is in the traditional territory of the Cree and Denesuline (Chipewyan) Indigenous peoples. It is the oldest settlement in Alberta. Many of its almost 1300 residents are Mikisew Cree, Athabasca Chipewyan and Métis.

On the shore of Lake Athabasca, Fort Chip is in the traditional territory of the Cree and Denesuline (Chipewyan) Indigenous peoples. It is the oldest settlement in Alberta. Many of its almost 1300 residents are Mikisew Cree, Athabasca Chipewyan and Métis.

The area’s Indigenous peoples’ involvement with the fur trade began in the late 1600s, with the Dene acting as middlemen between the First Peoples and the Hudson’s Bay Company. In 1778, fur trader Peter Pond built the first trading post in the Arctic Drainage System – and first white settlement in Alberta – on the south shore of the Athabasca River. Six years later, in 1784, small pox killed 90% of the Chipewyan people living in the area. Four years after that, in 1788, Pond’s post was moved to its present location on the north shore, re-named Fort Chipewyan, and became headquarters for the Northwest Trading Company. Alexander Mackenzie and John Franklin both used the community as a launching pad for their Arctic voyages. The Hudson’s Bay Company set up shop in 1815, marking the start of a six-year “war” with the Northwest Company for control of this precious natural resource.

The church made its appearance in 1849, when Oblate Father Henri Faroud chose Fort Chip for the Catholic mission. The Anglicans arrived in 1858, when Archdeacon J. Hunter visited. The Anglican church built in 1880 is still in use and is the oldest in Alberta. Opened in 1902, the Convent of Holy Angels Catholic Indian residential school was closed in 1974.

The Chipewyan and Cree were signatories to Treaty 8 in 1899, eleven years after the great famine and twenty years before the Spanish Flu swept through the community. Treaty 8 covers 84,000,000 hectares in northern Alberta, northeastern British Columbia and northwestern Saskatchewan, an area larger than France. While the Chipewyan and Cree peoples have lived up to their part of the treaty, abrogation of responsibility has largely been the settler’s response. Now, treaty rights are at the centre of disputes with the resource extraction industry.

Not surprisingly, history means a lot to the residents of Fort Chip. For them the issues raised by the oil sands projects are not new, but they are complex. There are no clear, step-by-step solutions. As was the case during the fur trade, when beaver pelts brought prosperity to some but not all, the wealth created by the oil sands has created divisions and led to differences of opinions. One of the community members mentioned the idea of a “resource curse”, referring to the many and varied conflicts and tensions that come from the extraction and sale of lucrative resources.

The tension between the economy and the ecology isn’t new either. The fur trade devastated the population of fur bearing animals. The oil sands pose a serious threat to the environment. Fort Chipewyan is downstream from the oil sands projects and some of its citizens are deeply worried about the impact on health and wildlife. Threats to land, water and animals in turn threaten traditional ways of life and core identity.

At the end of the 17th century names like the Hudson’s Bay Company, the North West Trading Company, Mackenzie, Pond, and Franklin dominated. Today, it’s Syncrude and Suncor. The names have changed, but the issues are largely the same. Bitumen has replaced beavers, but the unequal distribution of wealth and opportunity remains, along with all the environmental threats and social challenges.

Despite extravagant promises, the fur trade did not elevate the position of Indigenous peoples over the long term. Without a return to the treaty relationship and a recommitment to treaty rights and responsibilities, there is little evidence this current resource “opportunity” will be any different. Shared land and resources is not a commitment to share in exploitation, but a commitment to share in the stewardship and protection of the land for its own integrity, and for present and future generations, renewing both the spirit and the letter of the treaties.