Dying by the Sword – By James Loney

Theological Reflection – Sunday, November 10, 2013

James Loney is the author of Captivity: 118 Days in Iraq and the Struggle for a World Without War. It is a memoir about his work in Iraq with Christian Peacemaker Teams and his experiences as a hostage there. He is currently working on a Masters of Social Work at Wilfrid Laurier University.

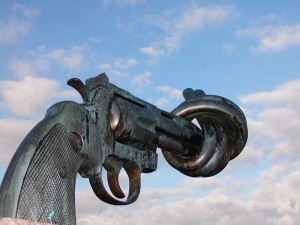

“Then the men stepped forward, seized Jesus and arrested him.” (Matt 26:51) The dreaded moment. They had two options. Fight to the death in desperate hope of escape, or surrender to torture and death by slow asphyxiation on a cross. An unnamed follower of Jesus decided to act. He took his sword and cut off the ear of the high priest’s servant. “Put your sword back,” Jesus commanded. “All who draw the sword will die by the sword.” (Matt 25:53)

“Then the men stepped forward, seized Jesus and arrested him.” (Matt 26:51) The dreaded moment. They had two options. Fight to the death in desperate hope of escape, or surrender to torture and death by slow asphyxiation on a cross. An unnamed follower of Jesus decided to act. He took his sword and cut off the ear of the high priest’s servant. “Put your sword back,” Jesus commanded. “All who draw the sword will die by the sword.” (Matt 25:53)

Before being kidnapped in Iraq, I used to hear this as a statement of moral caution and karmic reciprocity: if you play with fire, you’re going to get burned; or, what goes around comes around. Since then, I have come to see it as comment on the nature of violence itself. Violence irrevocably changes us; marks us forever; implicates, impugns, corrupts the deepest aspects of our being.

Our culture is constantly telling us we can use violence without consequence. If it is legitimate and necessary. If it is forced upon us, as a last resort, in self-defense. If it is for the protection of an innocent or to secure the common good. When purified by necessity and reluctance, not only is violence without consequence, it transforms into honor, and its practitioners become heroes. A hero’s violence is anodyne and antisepsis.

The Hunger Games, a runaway bestseller written by Suzanne Collins, is a typical example. The novel takes places in Panem, a post-apocalyptic nation located in the interior of the present day United States. Every year, one boy and one girl (aged 12 to 18) is chosen by lottery from each of Panem’s twelve districts. The youth are taken into an outdoor arena where they fight to the death in a televised spectacle called the Hunger Games. The protagonist-hero, 16-year-old Katniss Everdeen, takes her younger sister’s place after she is selected for the Games. A skilled archer and hunter, Katniss evades killing until the Games’ masters engineer a confrontation with her most lethal adversary. In the ensuing battle, she is forced into kill after the death of her friend and ally Rue. Katniss is deeply grieved by the loss of her friend, but experiences no internal turmoil with regards to her initiation into killing, or any of her subsequent killings. The violence she uses is just; it is therefore without consequence.

The Hunger Games is a breath-taking read. I read it across a summer day. When I was done, it left me deeply unsettled. I was so enmeshed in Katniss’ noble, conflicted and compromised struggle to survive, it took me awhile to figure out what The Hunger Games was doing. To see that it is part of the cultural lie that disguises the truth about violence: it is trauma, a shock to our being, a wound to the soul. Soldiers who kill, for example, are forever haunted by what they have done. They experience significantly higher rates of post traumatic stress with greater intensity. Captain David Grossman, author of On Killing, calls it “the burden of killing.” The vast majority of us, he says, have an instinctive aversion to killing which basic training must override if a soldier is going to be successful in his (or her) job. “Looking another human being in the eye, making an independent decision to kill him, and watching as he dies due to your action combine to form the single most basic, important, primal, and potentially traumatic occurrence of war.” (p. 31)

When I was held captive, one of our captors told me he was going to go on a suicide bomb mission. His home in Fallujah had been bombed, wiping out his family. Now he was a mujahedeen, a holy warrior of God dedicated to fighting against the coalition that invaded his country and shattered his life. The America soldiers would go to hell, and he would join his family in heaven, a martyr and a hero. It struck me in that moment that God had not created him—or any of us—for killing. Turning his body into a weapon was contrary to the purpose for which he had been created. He, like of all us, was given life for giving life, sharing love, creating beauty, healing. This, I now think, is what Jesus meant when he said all who draw the sword will die by the sword. He is telling us there is no such thing as violence without consequence. Violence destroys what is most essential to us, our life purpose, the call to love in the image and likeness of the God who created us. The God who “causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous.” (Matt 5:45) A God who loves good guys and bad guys in equal measure.

Put away your sword, Jesus says. Violence does not make you a hero. It destroys what you were created for. There is more than one way to die by the sword.