Playing Games

Jubilee Preaching Aid for September 14, 2025

Readings for the Fourteenth Sunday after Pentecost

- Jeremiah 4:11-12, 22-28

- Psalm 14

- 1 Timothy 1:12-17

- Luke 15:1-10

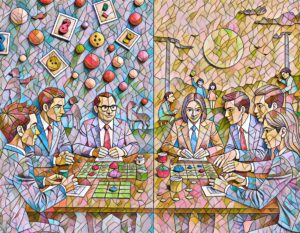

If you’ve ever played games with children (or adults!), you’ll know that different games require different kinds of skills. “Memory” is a simple game and yet it can be challenging for adults. As different cards are flipped up, can you remember what you saw two or three turns ago? Can you find the matching sets? “Cribbage” involves counting and knowing different ways to make points – with pairs or runs or adding up to 15. And “Yahtzee” is a game played with dice – a game of chance, that also includes some strategic choices.

Over the last 30 years, German-style board games have also become popular. One of the features of this style of game is economic competition, rather than random chance or direct conflict. In many of these games, players succeed by knowing how to manage resources and make trades. Each of these games has a different set of rules, and each game rewards a different set of skills.

Unfortunately, today many business leaders and government officials seem to approach their work like a game as well. The game is about collecting as many political points as possible, or gathering the most resources, and the rules are constantly being changed – usually by people who are already in the lead.

These games reward players who are successful at increasing income and minimizing expenses. Actions have costs in the real world, and yet in the “game” of economics costs can be externalized. This “game” rewards those who can make other players pay the costs.

The business practice of “planned obsolescence” is designed to force consumers to keep spending money, rather than out of any sense of “good.” Similarly, many products are designed to be disposable, rather than repaired. The loans that are available to low-income individuals and nations are often structured to make it unlikely that they will ever be repaid. And the legal language that governs these transactions is often inscrutable and unintelligible to common folk or across language barriers.

What is the point of all these games?

In the reading from Jeremiah this week, it’s as if people are playing games too, not with cards or dice, but with people’s lives. God looks at the games we play and calls it foolishness:

“My people… are skilled in doing evil, but do not know how to do good.”

And the Psalmist concurs:

“Have they no knowledge, all these evildoers who eat up my people like bread and do not call upon the LORD?”

The games our world plays reward the skill of doing evil, chewing up and eating people like bread. But this is not the only game we can play.

The English word, “economy,” comes from the Greek oikonomia, from household (oikos) + management (nemein). And this is a clue as to what economics ought to be about: not a game of winners and losers, but a way of managing a “household.” For Christians, that household does not belong to one team, one nation, or one business; the household is God’s. And today more than ever before, in our globalized world, we can be aware of the vastness of God’s household:

“The earth is the LORD’s and all that is in it, the world, and those who live in it” (Psalm 24:1)

In this household, it is impossible to externalize costs, because nothing is “outside.” In fact, we all win when we manage this household well: everyone eats, and the root causes of conflict are reduced. People are free to create and celebrate out of their passion rather than fear of scarcity or competition. In this game, we learn the skill of doing good.

The concept of Jubilee is a law of God’s economy. Jubilee resets the board – not as an act of charity but as an act of justice. The cancellation of unjust debts (and their interest payments) is a law of God’s economy because unjust debts and their interest payments do not add anything to the resources of the household. Interest payments simply redistribute wealth from one player to another.

Instead, Jesus shows us something of what God’s economy looks like. In the parables of the lost sheep and the lost coin, Jesus describes a person-centred economy in which the loss of even one is not an acceptable cost of doing business. The shepherd foolishly abandons the ninety-nine to save the one. (Where is the risk management consultant?) The woman does not write off the one coin, but continues searching until all ten are found. (Has anyone conducted a cost-benefit analysis here?) In these parables, Jesus shows us a different way of playing the “game” of economics, in which no loss is negligible, no harm is acceptable, and no sacrifice is too great in the management of God’s household for the well-being of all.

Kevin Guenther Trautwein is a member of KAIROS Prairies North who lives in Edmonton, Alberta, subject to the promises and commitments made in Treaty 6, by the grace of God, by the gifts of the land, and by the faithfulness of the First Peoples who have kept and cared for this land since time immemorial.