Water flows, connects and knows no borders

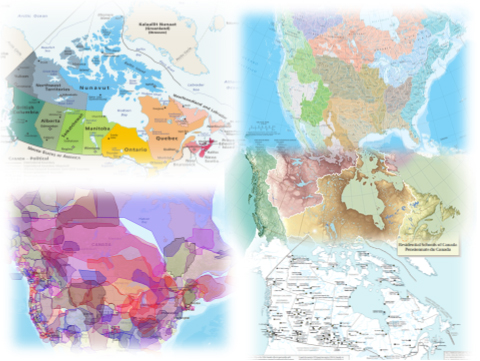

I hadn’t realized how maps shape ones perspective of place and in turn how one then relates to that place. On October 14th, I attended a KAIROS event in Halifax on the topic of Reconciliation In Our Watershed. At one of the group sessions we reviewed, discussed and reflected on six different maps with different information on the territory most of us identify as Canada. Five of the six maps presented were mostly unknown to me. Juxtaposed, the contrasts that stood out to me most came from three maps that exhibited Canada as I know it, continental watersheds and traditional Indigenous territories.

We were asked to look at these different maps and answer in small groups a few reflective questions, such as: Where are the five main watersheds and which watershed are you in now? If you were a policy maker, which of the maps would you utilize most? Which maps do you see when you think about the way we exist within creation or the natural environment? Someone in the room said they navigate territory based on the road systems and how to get from work to shopping to home, in the quickest way possible. I realized that I too most frequently view the land this way. Indigenous nations used the major waterways for trading and the watersheds have and continue to define so much of their relationships to land usage, their culture and language. This organic and place-based way of relating to the land, was made apparent to me while viewing one of the maps which showed overlapping, irregular shapes defining all the various Indigenous nations’ traditional territories (see interactive map at www.native-land.ca). The territorial layers have not been defined by straight lines; they overlap one another and have been formed based on intimate relationships to landscapes and to neighbors. The information depicting traditional Indigenous territories is absent on colonial maps, which have been drafted to only show provincial and federal jurisdictional legal boundaries.

Contrasted against one another the political maps clearly show a complete disregard for Indigenous existence and ways of life and a new reality forcefully placed on top. The colonial government carved up the land, created borders and distributed private property to settlers, attempting to destroy traditional connections to land. These manmade (male-made) borders cut through natural flows of water, traditional human movement, and Indigenous communities. I found myself asking why our education institutions limit the types of maps taught in schools. Why the societies of the first inhabitants have been largely written out of our textbooks. I was only taught to view the territory we call Canada through provincial and territorial divide; taught to view creation through the lenses of colonialism. When viewing these five maps side by side one can see how the standard map of Canada is mostly disconnected from the landscape and waterways and disregards Indigenous sovereignty.

Contrasted against one another the political maps clearly show a complete disregard for Indigenous existence and ways of life and a new reality forcefully placed on top. The colonial government carved up the land, created borders and distributed private property to settlers, attempting to destroy traditional connections to land. These manmade (male-made) borders cut through natural flows of water, traditional human movement, and Indigenous communities. I found myself asking why our education institutions limit the types of maps taught in schools. Why the societies of the first inhabitants have been largely written out of our textbooks. I was only taught to view the territory we call Canada through provincial and territorial divide; taught to view creation through the lenses of colonialism. When viewing these five maps side by side one can see how the standard map of Canada is mostly disconnected from the landscape and waterways and disregards Indigenous sovereignty.

Viewing the maps, and considering the new information they provide, left me with new questions. What would a new relationship between the Indigenous and settler population look like? How can I live a life in closer harmony to creation and daily give thanks for the gifts provided to me? What is my watershed and how can I connect to it in a deeper way?

We began the day in breakout groups and I attended the Watershed Protection and Legal Action walk. We began our walk in front of the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal. Our facilitator provided us with an overview of the legal processes around water and environmental protections, how the courts perceive environmental issues and Indigenous rights and how the Crown maintains ultimate decision-making control over land and water. The day concluded with a circle of holding hands with Dorene, a Mi’kmaq Grandmother, sharing a water song and prayer. Dorene recommended a daily sacrament to help us reconnect with water and creation. Fill up a glass of water in the evening and place it next to your bed. The following morning arise and say a small prayer before you drink, “Water I thank you. Water I love you. Water I respect you.” It is through these sacred acts that we connect with creation and build new relationships with it and each other, relationships that no map can define.

Eva Boucek was born in Montreal to Czech immigrants who disembarked on a flight stopover leaving Communist rule. Privileged into the colonial system of Canada, and only in recent years learning about the true history of immigration policy and its effects on indigenous people, she is interested in prefigurative solutions that lead to reconciliation. Most recently she lived on a remote island off the Pacific Northwest (Klahoose territory) working at a democratic free school. She also worked overseas with refugees.