Spirited Reflection: Forgiving our debtors

Living in Scotland was my first time praying in ecumenical groups. You might imagine, despite theological differences, that we always had the Lord’s Prayer in common, but I encountered differences between the English and Scottish versions, especially the line prayed in Scotland “Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors”.

There are various ways to translate this. ‘Trespass’ implies God as property owner and us as peasants trampling the formal garden, scrumping apples from God’s orchard. The callback to the Garden of Eden is clear, and it’s easy enough to understand trespass referring to various sins.

But translating the line with ‘debt’ and ‘debtors’ gives a different emphasis. Debt is a condition of everyday life, from individual debt managed through mortgages or credit cards, to the debts of nations.

Our modern global economy depends absolutely upon the creation of debt, upon systems of borrowing and interest that create more economic “value” divorced from actual goods – and dependent upon constant “growth” in this circularly self-maintaining system.

On the Theology of Money, ‘Non Nobis, Domine’, 17

As young people go off to university or as people acquire houses and cars, we celebrate these milestones, appropriately so. It seems unkind to think of these in economic terms – as the creation of debt. Yet, this is also part of the way that these lives are being transformed. Debt is an enormously powerful force in our economy, and this power shapes our culture, our values and customs.

The debt language in the Lord’s Prayer works as a metaphor for a wide category of sin, but debt itself is a specific wrong.

The lending of money for interest is condemned throughout scripture. By implication those who owe money are participating in sin – but those who lend and expect increase are greater sinners.

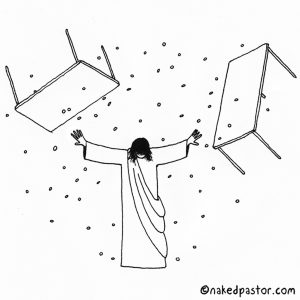

In Matthew 18:21-35, Peter asks about forgiveness. Jesus prescribes forgiveness far beyond reasonable accommodation, then offers a parable of the Kingdom. A powerful king is settling accounts with a slave who cannot pay. This slave is forgiven his colossal debt but then refuses to forgive the smaller debt of a fellow slave.

The Kingdom of Heaven offers bountiful forgiveness. The king resolves the debt with grace and mercy, but when the slave is vicious towards his own debtor and the king learns of this, he rescinds his forgiveness and sends the slave to be tortured until he pays his debt. The story ends with no one any happier, but the worst sort of punitive justice achieved. If this act of forgiveness represents the Kingdom, it suggests that something more is required!

What would Jesus’ original audience have felt? The absurdity of the first debt? Terror at the king’s demand to repay? We might wonder about the impact of the demand and subsequent forgiveness on the debtor. The king saw the slave’s actions as merciless, but those who have felt the crushing power of debt might have seen pragmatism – a survival logic to be so vulnerable never again. Then the capricious king decides to collect on his debt after all – because the slave has not made the same choice to forgive, apparently an unstated condition.

But there is another set of actors. It is the community of fellow slaves that reports the injustice and brings down the king’s wrath. Are they acting out of a desire for justice? Jealousy? Out of solidarity with their imprisoned fellow? Are they also debtors to the first slave, and next in line to be imprisoned? Whatever the case, they seek out the king’s power over them all, and he invokes a moral equivalence to justify his violence.

We know, to some extent, that debt is arbitrary. University students of some nations must borrow heavily while others graduate with no personal debt. Some must go into debt for medical care, while the same care is available across a border, paid by taxes. The parable shows it being forgiven and then re-imposed at the whim of a king. Debt creation and relief are largely political issues, used to control and reward, not just a matter of economics.

The Bible suggests that debt is either fundamentally unjust, or inevitably creates the conditions for injustice in the absence of mechanisms like the Jubilee year and prohibition on lending for interest. The Lord’s Prayer offers daily signs of the Kingdom of Heaven, including forgiving debts and accepting debt cancellation.

Let us seek to make a world where debt no longer restricts life and relationships, and let us also consider which debts we have the power to forgive.

Peter Haresnape is the General Secretary of the Student Christian Movement of Canada, an ecumenical justice-focused movement that works with students and young people to put into practice the liberating faith of Jesus. Peter is a member of Toronto United Mennonite Church and the Christian Peacemaker Teams. He thinks Jesus’ approach to financial management (paying temple tax with fishy currency) sounds great.