Reflections on the birth of KAIROS #KAIROS20

An anniversary is a good time to remember our roots. It is also a good time to look for a continuum from what the founders hoped and prayed KAIROS would become to what it is now, twenty years on.

I was there at the beginning. I know why KAIROS was formed; I know what went before. I lived through the negotiations that brought it into existence; not only was I present, but I chaired many of the meetings. I think of myself, in fact, as one of the midwives present at KAIROS’ birth.

Twenty years ago, I was on the national staff of The Presbyterian Church in Canada, but decades before I became a staff person, I was a member of the ecumenical justice community. It was made up of women and men (some like myself volunteers representing our national churches) working together from the early 1970’s to form the “justice coalitions”, the roots of KAIROS. I became a member of this community in 1975 as the Presbyterian representative on the executive committee of Ten Days for World Development. Several coalitions engaged in research and advocacy on international human rights, others in partnership with Indigenous peoples, or grassroots global education. One brought together resources for international development, and there were more.

For twenty-five years or so the churches worked together in this way, and there were some notable achievements. The coalitions spoke to government on human rights issues in Central America and elsewhere. They advocated for a new Canadian policy for refugees. They were in the forefront of the sanctions movement against apartheid South Africa through shareholder resolutions to Canadian companies invested there. In addition they raised awareness in grassroots groups across the country concerning sustainable development, and the care of the environment, and voiced support for Indigenous rights.

However, despite the coalitions’ success, by the late 1990’s, there were growing challenges, and the future of ecumenical justice work was looking increasingly threatened. Most significant was the reality that church membership and contributions were declining; there was less money to support the ecumenical work, and less money to support denominational staff, part of whose jobs was to attend the proliferation of meetings the coalitions required. Then there was the dark cloud that hung over several of the churches that had been heavily involved in the residential schools. As more and more became known about the reality of those schools, and their tragic legacy, those churches realized they were liable to face potentially crippling lawsuits. They knew they were in a very vulnerable financial position.

It was not only the churches’ financial situation that led to the call for changes to our shared justice work. It was becoming increasingly apparent that the coalition model, given our shrinking resources, was ill suited to evolve to meet new challenges. The care of creation was becoming ever more of a priority as climate change moved from the fringes to a mainstream concern, yet there was no sustained ecumenical work on ecological justice. And, increasingly, we were coming to realize that we were devoting far more staff time and resources to advocating for Indigenous people and the marginalized of other countries than we were to advocating for Canada’s own First Nations. We all agreed on the imperative to work on these emerging priorities, but we knew there was no new money. And cutting back existing – and entirely valid – programs was very hard.

Finally, as the century came to a close, several churches who were major funders of the coalitions told their ecumenical colleagues that the writing was on the wall. The time had come for a radical restructuring of our shared justice work that would reduce costs. Failing that, the big churches would be forced to cut back, and one way or another, piece by piece, the work would come to an end. The clock was ticking.

What happened next is all about organizational structures and processes, and I am well aware that those who read this are (like me) rather impatient at time spent on either. Accordingly, I will try to skate quickly over the next few years of negotiations.

From CPAC to CCJP

From almost the beginning, the churches had recognized the need for an annual gathering of all those involved in the coalitions – churches, staff, coalition board members – to get everyone on the same page especially with regard to coalition staff salaries and personnel policies. This gathering was called the Coalitions’ Personnel and Administration Committee (CPAC). This was the one body which brought the funders (the churches) and the programs together in one room, and it was in this forum that we had heard for a number of years various voices asserting that “we can’t carry on in this way!”.

It was, therefore, at a CPAC meeting late in 1999 that the decision was made that it was the logical body to undertake the restructuring which now seemed inevitable. As it happened, the co-chairs of CPAC in 1999 were Arie Van Eek, representing the Christian Reformed Church, and myself. Arie was not based in Toronto, where most of the meetings took place, and so a lot of responsibility for steering this process fell to me.

It was a hugely difficult task, with many players, and numerous moving parts. Sometimes emotions ran high. To get all the churches to buy in, we had to move by consensus, which is never easy. In addition, many of the individuals (including myself) who were tasked to dismantle the coalitions were extremely conflicted. We represented churches – the funders – but we had been personally involved in the coalitions. We believed in the work, in the coalition ethos of collective decision making, and the coalition staff were friends. Many of us dreaded the potential fall-out for the staff involved, and the damage that might be done to vitally important work. As the possibility of radical changes became clear, the coalition staff association began to consider unionizing; long-time colleagues were drawing apart.

It would have been very easy for those of us who were entrusted with the restructuring to back away and resign, pleading the pressure of other work. A number of those watching the process back in our church offices saw the problems mounting and predicted we wouldn’t have the backbone to make the changes necessary; they thought we would throw up our hands, in which case, the whole thing would fall apart. One church referred to the task we had taken on as equivalent to “cutting the gordian knot”; people feared the churches would “cave, and let the work topple like dominoes.”

However, God willed otherwise. Ours was a determined steering committee that put in many extra hours, and we were aided by several consultants and the United Church’s legal team. Over several months, this effort brought us to a consensus that we would dismantle the coalitions in favour of one structure, an organization with the same membership as CPAC which would set the direction for the churches’ justice work, and provide the funding. Implementation of the program would be led by an executive director supported by program staff.

We were much clearer on the new structure than we were on how the program might change. This is certainly not surprising because the most sensitive issues related to the work people had given years to developing. Nearly all the difficult program decisions were punted down the road, and took place in the first year or eighteen months after the new organization came into being. We did lose staff, and there was some bitterness, and some sadness.

In November 2000, CPAC reconstituted itself as the “Canadian Churches for Justice and Peace” (CCJP) which would be an “ecumenical partnership, with the purpose of assisting the partners in making their witness of faith to God’s mission of justice, peace and the care of creation.”

The participating churches negotiated the terms of, and then signed, a legal Memorandum of Agreement, which among many other things defined the role of the United Church in administration, personnel, and finance. By this Agreement, the churches transferred the direction of their ecumenical justice work from the various coalition boards to the new organization, and agreed to form a provisional “First Board” as a bridge from CPAC (essential an annual meeting) to an organization, the CCJP. Arie Van Eek and I continued as co-chairs.

From CCJP to KAIROS

The first thing we did was to contract Jeanne Moffat, widely respected for her role in leading Ten Days for World Development, to take on the myriad details of the re-organization – especially the personnel issues. Jeanne was with us for six months, and in the spring of 2001, the CCJP advertised for its first executive director to continue the work on the foundations that Jeanne had prepared. We were moving into the second phase of the restructuring – the program, and Pat Steenberg from Ottawa was engaged to lead us forward.

In September 2001, we had a meeting scheduled of a small planning group: our new executive director with Jane Orion Smith, the Quaker representative on the CCJP, and myself. The task was to prepare for the next meeting of the Board, and this felt like an important meeting – a milestone. Nearly two years of meetings and negotiations, of frustrations and prayers had finally reached the point where we could plan for the new work that was to come. The meeting was scheduled for September 11.

September 11, 2001… I remember it as a beautiful early fall morning, but it proved to be a day that would change the course of history, and cast its shadow over the next decades. Our meeting was in the Friends’ House, and we had a few productive hours working in Jane’s office. Then a colleague came in to say that something terrible was happening at the World Trade Centre in New York. My memory is that the planning meeting wrapped up pretty quickly!

That aborted meeting is the last one I remember with clarity, although I do recall the vote that took place at a Board meeting not long afterwards when a new name for the “Canadian Churches for Justice and Peace” (CCJP) was approved. The name “KAIROS” was the hands on favourite choice from a short list proposed. The one-word name emphasized the reality that this was a distinct stand-alone organization; the churches’ role, and the organization’s focus was brought out in the addition “an ecumenical justice initiative.”

As we moved into 2002, the executive director took on an increasing share of the work and the leadership. Although I was still a Presbyterian representative on the Board, my involvement was much less intense. I was chiefly aware of what happened with coalition staff – those who stayed on in KAIROS, and those who left. I am grateful that many of them have remained my friends.

As I recall, my feelings at the time were mixed, and I think this would be true of most of my colleagues from the churches. First of all we were relieved that the worst outcome – the disintegration of the ecumenical justice work – had been averted, and we were thankful that the months of negotiations had not proved a waste of time. We were proud that the churches’ shared commitment to ecumenism and to justice had held them together and carried them over the obstacles that cropped up during the process.

I was personally very grateful to the stalwarts on the steering committee – and the staff in my own office – who supported me throughout. Everyone put in many extra hours of what sometimes seemed like fruitless labour to bring this new organization into being. (Looking back now, I am saddened by the fact that a number of the church representatives who served with me on the small steering committee have since passed away. We lived through a difficult time together; I regret that as we all retired we lost touch.)

But as for the future of the new organization, KAIROS, only time would tell.

KAIROS today

Twenty years ago, I was very ambivalent about what we had created because it was far from clear how much of the coalitions’ work would survive in the new configuration. As the adage goes, you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs. While I was cautiously hopeful, I was only too conscious of the eggs that had been broken. But if my feelings at the time were mixed, what are they now? Was all that effort worthwhile? Is KAIROS on its way to fulfilling the hopes the churches had for it twenty years ago?

My answer from what I have heard and seen for myself is a very definite “yes.” I believe now that our effort decades ago was certainly worth it. While it is true that some important pieces of work were left behind, KAIROS as it is today seems to me to be well on its way to fulfilling the goals the churches had for it. Here are three examples of current program to explain why I believe this.

First of all, it has been able to address the new priorities that the churches twenty years ago saw were being neglected. Both the care of creation and justice for Canada’s First Nations have been a focus for KAIROS from its inception. I may be wrong, but it seems to me that increasingly the principal focus is more on the second than on the first. If that is so, it would be justified by the reality that both governments and other very well-funded NGOs are leading the way on ecological issues. And, in my view, standing in solidarity with Canada’s First Nations as they struggle to gain redress for centuries of injustice must be at the heart of KAIROS’ mission. Both our churches’ history with the Indigenous people of this land, and the present urgency to act now after a century of delay and neglect demand nothing less of us. And the success of the Blanket Exercise speaks for itself!

Second, KAIROS’ program has found the way to break down the geographic and sectoral silos that hindered the coalitions’ work. The “Women of Courage” with its focus on women’s challenges and achievements in three different parts of the world recognizes and affirms the central role that women everywhere have in bringing about social change. It also highlights the reality that many local problems have universal causes; they are the local manifestation of a global inequity that produces similar problems in many other countries – including our own.

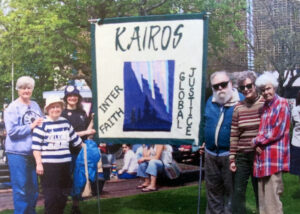

Finally, KAIROS is finding ways to mobilize faith-filled people across the country. Moreover it is encouraging the church-related groups to make connections with people of conscience wherever they find them.

This spring I have been sitting in on the webinars bringing together local groups who work in solidarity with their areas’ migrant workers. I have long thought that the migrant workers in our midst are a great “on-our-doorstep” illustration of the global interdependence and food security that we talked about in Ten Days all those years ago. But KAIROS has gone many steps further than Ten Days. It has built on its own church-related network (in part a legacy of Ten Days) and encouraged them to reach out to other good-hearted people in their communities to form local alliances in solidarity with migrant farm workers. It is a “movement within movements” – the multiplier effect that can bring about real change.

Local groups interacting with migrant workers is both a hands-on practical way of tackling global issues by acting to address local problems, and the very best way of learning about how the world works – how the systems in place work in favour of the few at the expense of the many. And it is also the very best way to put a human face on economic abstractions. As I watched the webinars I warmed to the descriptions of the barbecues and “welcome back” gatherings for these workers who spend long months away from home growing food for our tables.

In conclusion…

I found the opening sections of the Strategic Plan on the KAIROS web site very good reading. I note that plan ended in 2020, and I hope that a new one will include a similar description of KAIROS – largely because so much that is there reflects the aspirations we had for the new organization we launched in 2001.

l will reference one part that particularly spoke to me:

From the “Core Identity”: the affirmation that KAIROS is about connections –connecting churches, issues, regions, communities; about integrating analysis with reflection, and both with action; about integrating action on one level (church-leaders issuing a statement on a matter of justice) with local action addressing the same inequity; about connecting one region with another, one country with another; about building bridges to other faiths and people of conscience, “who we not only want but need” to enable effective and credible reflection and action.

And from “Who we are” on the web site –

We bring people together: the churches as institutions with their collective voice, and the church as a spirit-filled movement of people…

Movements are organic. The movement we are building will grow and change. Twenty years ago, the churches wanted to create an ecumenical partnership to make a witness of faith to God’s mission of justice, peace and the care of creation. Looking back, I believe their focus was mainly on the institutions as the primary actors. Twenty years on, we know that institutions still have their place, but KAIROS, representing a spirit-filled movement of people may well be showing us another way of being God’s presence in the world.

Written by Marjorie Ross.