Join your community for Candles for COP

For the Love of Creation invites groups across Canada to host Candles for COP – candlelight vigils in their communities from November 15 to 17, marking the first weekend of the COP29 climate conference, held November 11-22 in Baku, Azerbaijan. KAIROS is a member of For the Love of Creation.

These vigils are a way to share hope for truly transformative action at COP this year. Learn more about this campaign, add your event to the map or find a vigil near you. Visit For the Love of Creation’s Candles for COP: Vigils for Climate Justice.

To inspire you, we are sharing an excerpt from Chapter 4 of Leah Reesor-Keller’s book Tending Tomorrow. Leah is KAIROS’ Transitional Executive Director. In this chapter, Leah writes about how attending a Candles for COP vigil in 2023 with Durga Sunchiuri, her friend from Nepal, helped remind her:

“What matters is the commitment to keep showing up with others, to believing together that it is worth striving for things to be different from how they are.”

“Renewing Our Hope and Transforming Despair” – excerpt from Chapter 4 of Tending Tomorrow

A friend who is in his seventies recently told me about his concerns that our Global North economies are not transitioning away from fossil fuels fast enough. “The IPCC report says we might already be past the 1.5 degrees Celsius that will lead to catastrophe!” he said. The 1.5-degree threshold for limiting warming on our planet was first laid out in the Paris Climate Accords in 2015 and is monitored by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a global body of scientific experts. “The global average temperature is rising even faster than predicted.”

“I know!” I snapped back, irrationally irate at this concerned person. “And whether it passes that point or doesn’t, I’ll be here living in that future, with my children.” I like to think that I am a patient person, someone who can hold space for others to express fears and concerns. But in that moment, I had no space to hold anyone else’s anxiety that the world will simply end if we cross those tipping points.

Because the world itself will not end. It is the filaments and tendrils of life on our planet—the human, plant, and animal worlds that it sustains—which are at risk from the changing climate. As my son assured me one day, we don’t need to worry too much about being sucked into a giant black hole, because our sun has a relatively small mass and is unlikely to form a particularly large black hole. Our planet of rock and water will be just fine, spinning on its axis circling our sun for millions of foreseeable years. Unless, of course, the theory of the universe ending in a vacuum decay turns out to be true, and a quickly spreading bubble of vacuum decay happens to blink everything out of existence. Or a nefarious meteorite crashes into the planet, in which case it really may be the end of the world.

On one hand, we’re suffering from too much water, as the polar ice caps melt into the ocean and the salty waters creep up over islands and coastlines around the world, pulling cities and whole cultures into the sea. Yet we’re also suffering globally from not enough fresh water. Sometimes called the “third pole” of the world, the snow cover and glaciers of the strip of mountains in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region are the source of freshwater for a quarter of the world’s population.[i] The Ganges, the Yangtze, the Mekong, and many other rivers throughout South Asia and China are connected to the water supply of the Himalayan region. This mountain region spans Afghanistan on the western side and continues east through Pakistan, India, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. The water in these mountains, in the form of glaciers, snow, and permafrost, sustains life for people, plants, and animals across the Asian continent. But it is at grave risk of drying up as snowfall patterns change and glaciers melt at unprecedented rates.[ii]

During the five years I lived in Nepal, I depended on this water for my daily needs. I crossed river canyons on swinging metal suspension bridges and met with farmers whose livelihoods depended on the water linked to the mountains and the cycles of monsoon that replenish the snows and irrigate the terraced fields. In my vacation time, I trekked up into the high Himalayas. I love the Annapurna region best for its stunning beauty and its diversity of human, animal, and plant life. Annapurna means “full of grain” in Nepali. This mountain range forms one part of the Himalayas, with lush green foothills winding up to the white peaks at the top of the world. Glacier-fed rivers and springs, along with the seasonal monsoon rains, feed fields of rice, buckwheat, and corn. I remember one October visit in particular, during the Dashain festival season when the fields were golden with ripened rice. Tall bamboo swings lashed together with ropes dotted the landscape, set up for playing and reveling in joy at the harvest season.

When I think of those villages below the glaciers, I am left wondering whether this heating climate will unleash, as seems inevitable, an overwhelming flood that will sweep away everything instantly in a glacial lake outburst as meltwater overflows the natural dams in the high mountain areas. Or if the foothills are somehow spared the flood, will the springs and rivers dry up as predicted, with significantly less water by 2100?

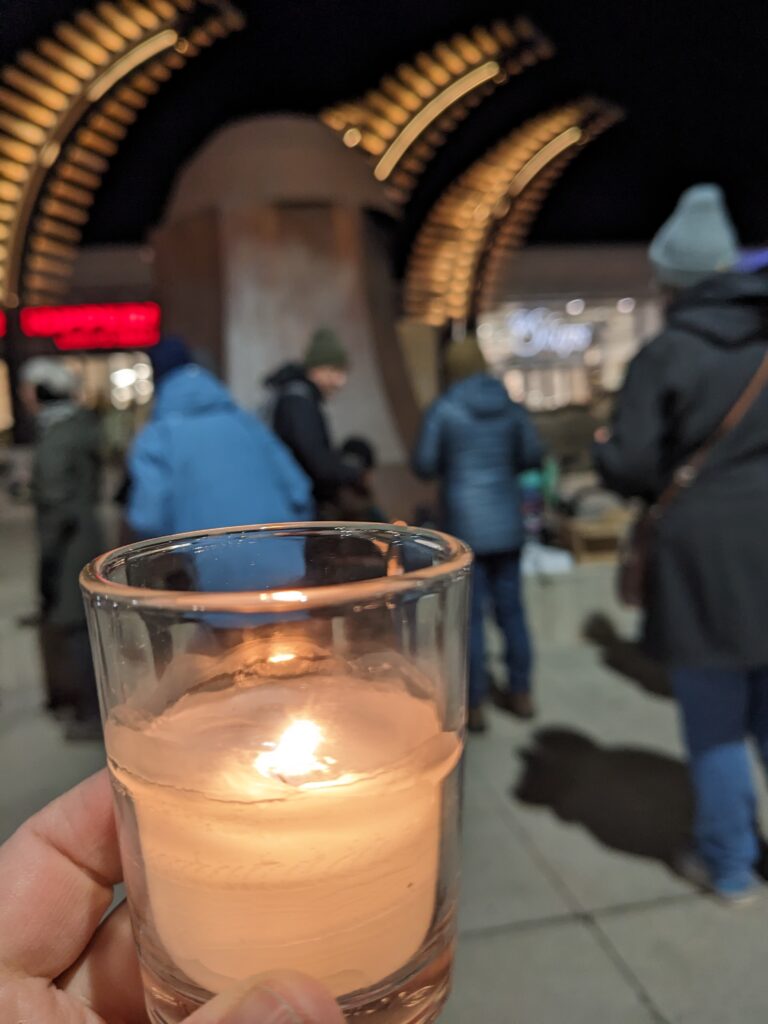

An old friend and colleague from my time in Nepal, Durga Sunchiuri, filled me in on how the climate crisis is intensifying in Nepal even in the span of the six years since I’ve moved back to Canada. Durga stayed at our home on one stop of his cross-Canada climate action advocacy speaking tour with Mennonite Central Committee, a nonprofit organization engaged in relief, development, and peacebuilding around the world. Shortly after he arrived, I went with Durga to a climate emergency vigil in the Waterloo public square. A group of about twenty figures bundled up in coats and hats cupped tealight candles in glass holders as they gathered in front of a single standing microphone and portable speaker.

The vigil, organized by a local interfaith climate advocacy group, was part of a series of vigils in the lead-up to COP28, the 2023 round of the United Nations Climate Change Conference where countries including Canada and Nepal negotiated emissions targets and contributions to the UN’s Loss and Damage Fund. Historically high-emitting countries, including Canada, are now responsible to contribute financially to the countries, including Nepal, who are most affected by climate change yet have contributed the least to its cause.

My friend Durga shared stories of mountain villages whose springs have dried up, requiring mostly women and girls to spend hours carrying water from lower elevation rivers and springs. Insects affected by the changing conditions move to new territory, wreaking havoc on crops that never used to face pest challenges and bringing outbreaks of disease to new areas. Mosquito-borne dengue fever is sweeping higher-elevation areas of Nepal that previously were too cold for the mosquito species that transmits the virus. Rainfall comes unpredictably in cycles of drought and flooding. The Himalayas are visibly less snow-capped and more bare, with more rock face showing through.

It was jarring to compare the present and emerging water crisis in Nepal to the situation in Canada. Before the vigil that evening, we had sat around our dinner table with Durga chatting about my spouse’s work in municipal carbon reduction. Luke is trying to convince hockey arenas to use a new technology to make the ice with cold water instead of hot water. Building the necessary buy-in is hard work. In Canada, where hockey is sacrosanct, arena managers are hesitant to try anything that might affect the ice quality. It feels absurd: that this is the level of discourse about climate change in our Canadian city, and that the energy and water resources needed to sustain this cultural fixture have any kind of priority in the global climate fight. Yet as winters in Canada become warmer, with more spikes and shifts in temperature, natural ice on ponds and outdoor hand-flooded rinks becomes more and more unreliable. In 2023, for the first time since it opened fifty years ago, the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, which becomes the world’s longest skating rink in winter, didn’t open for skating. The ice was too unstable. It’s a mind-boggling cycle: energy overconsumption in Canada and other wealthy nations that is driving global climate change is increasing Canada’s demand for energy to maintain its historically cold-climate traditions of skating and hockey.

Durga’s short address at the vigil was followed by ten minutes of silent reflection. Shrugging my shoulders to brace myself against the late November chill, I thought about this vicious cycle of energy consumption and global impact as I watched my flickering candle struggle against the wind. Standing there in the town square, in a spot where the annual outdoor rink would be set up a few weeks later, hope for change felt as distant and hazy as the Himalayan peaks I used to glimpse from my home in the city of Kathmandu.

Green Party leader and member of Parliament Elizabeth May was a surprise speaker at the vigil that night. She reminded us that in the past, the world has acted together to protect the environment. After controls were put in place through UN negotiations in the late 1980s, consumption of ozone-depleting substances has significantly decreased, and the hole in the ozone layer has peaked in size and is trending downward. Change is possible. Global cooperation on a large scale has happened and could happen again. The climate fight is not a lost cause. Still, in the volatility and shifting alliances of today’s world order, global cooperation can sure seem unlikely.

***

It feels overwhelming—the magnitude of it all, and how small and powerless I feel to act. On my worst days I chuck empty peanut butter jars into the trash instead of doing the sticky work of washing them out for recycling. Because in light of the challenges brought about by our changing climate, what matter are two extra plastic containers in the landfill? They’ll end up there eventually anyway. It’s my bold act of defiance; why am I working so hard to reduce my personal use of plastics, to buy clothes secondhand, to eat less meat and dairy, to use the car less? My personal actions for a more sustainable, lower-carbon lifestyle feel like meaningless toil in the face of the global oil and gas industry and the violence of warfare that destroys people and the environment. As parents with two young kids who need lots of hands-on care amid the full weight of our work expectations, my spouse and I face long days and exhausted evenings just trying to keep everyone fed reasonably healthy food and do our best to keep on top of laundry, dishes, and the occasional vacuuming. At 9:36 on a Thursday evening, I don’t have the energy or the willpower to wash out those jars anymore. It feels futile.

And still, the signals of our changing planet haunt me. A balmy 20-degree Celsius day in November feels sinister in its unseasonable warmth for Ontario. Sleet in May that unleashes a snow of falling cherry blossoms makes me wonder whether it is just bad luck or whether earlier, warmer springtime weather is drawing the blossoms out too soon, making them vulnerable. I plant milkweed, marigolds, zinnias, and other butterfly-friendly species, hoping to welcome the monarchs on their way; some years I’ve seen a few monarchs and a handful of other butterflies, but this past summer I saw a lone monarch in my garden. I was equal parts delighted to see this orange-and-black visitor and unsettled that it was late August and I had seen only this one. The challenges facing us in the present and the future push me to apathy, disengagement, and despair. Sometimes it is too much to hold.

I’m not alone in this unsettledness, a constant hum of grief and worry about what we humans are doing to each other and to life on our planet. Climate anxiety, as this feeling has come to be called, is a rational response to the multiplying effects of climate change. In a 2021 Lancet Planetary Health study of young people in ten countries, researchers found that two-thirds were very or extremely worried about climate change, and three-quarters said they think the future is frightening. The study authors stress that these are rational responses to the threats facing us globally, yet they also note that this burden of anxiety and worry takes a toll on mental health in a way that is not easily solved.[iii]

Somehow, we have to find our way forward, through what feels overwhelming, to take action anyway. One of the insidious things about despair is that it is paralyzing. It assumes that the outcome is fixed, that nothing can change it. Especially when the challenges feel so huge and so distant from us, despair can lead to disengagement and apathy—these feelings that so many of us struggle with. Paradoxically, facing these challenges with eternal optimism can also lead to the same place of disengagement and apathy. If you think everything will turn out fine, why take any action at all? Perhaps the only way forward is with a gritty, grounded kind of hope, one that looks clear-eyed at the challenges and is willing to take the next step, and the next, to act in accordance with our values regardless of whether the outcome seems fixed.

For many of us, we know how to live differently in a warming and conflicted world and are taking steps to do so in our daily lives. But in our quest for being good, for doing things right, we can get so caught up in trying to make changes in our own lives that our energy and focus shift from the centers of power where needed systemic change can occur. I wonder how Doris Longacre Janzen, author of the iconic 1976 More-with-Less cookbook, might feel about where we are today. Her book on cooking and eating simple meals, with lifestyle suggestions to live more lightly on the earth, is more relevant than ever. It’s a guide for North Americans to shift away from a food consumption lifestyle that requires five Earths to sustain it. It has sold nearly one million copies, finding traction with people looking to live and eat differently than the culture of consumption around them. But decades on from its publication by the very same publisher of this book, we’re still bringing cloth bags to the grocery store and finding three ways to use a leftover chicken carcass while the world is burning. On the one hand, this could look like a failure of the book’s vision. But we can also look at these small, personal changes—transforming the habits of readers, one at a time—as something worthwhile regardless of larger outcomes.

We need both the ways of living as if the future we want is here and the understanding that we’re in the imperfect space of the not-yet. We need to have grace for ourselves while we keep the focus on bigger advocacy goals that can have a longer-term impact beyond one household’s consumption patterns, such as advocacy to expand city public transportation and cycling infrastructure, and pressure on federal governments to make progress on global emissions reduction targets. In small and big ways, we have to keep taking the next necessary step and not lose sight of what must change if the future is to be different from the trajectory it is on.

***

Hope matters because it keeps us going. It keeps us surviving and dreaming that things can be different from how they are. Hope is the faith and belief that another way of living, another way of existing together on this planet, is possible. In the face of the climate crisis, giving up in despair is the worst possible outcome. Despair means giving up, accepting that how things are is how they have to be. Tending the embers of hope, fueling the sparks and flames that grow and falter and grow again, is our essential task. As I engage more deeply in this struggle, the further I move into joy and meaning and beauty amid suffering, into grounded hope that keeps going in the face of despair. Dreaming, imagining, creating, tending . . . these are all ways of living the world we want into being. If we can’t do this in little ways, home ways, community and family ways, how would we do it in big ways? We have to practice and build it, over and over again. Hope is the courage to show up for the ordinary actions, believing that something else is possible. Taking the next step, and the next, toward what could be.

My worst days aren’t easy. But on some of my best days, it is taking simple, hopeful actions that keep me feeling rooted and grounded. It’s finding joy in riding my bike on the trails and newly developed bike lanes to get around the city. It’s taking the commuter train into Toronto because it’s so much more pleasant than driving the crowded highways. It’s showing up with others for acts of care and solidarity, like bringing food to friends who’ve had babies or lost family members. It’s living in a way that centers community, people, and connection to the land not because “we have to fight climate change” but because living this way brings life.

***

I almost didn’t go to the climate emergency vigil with my friend Durga. I was tired. I had worked late and missed putting my kids to bed other nights that week. It was a blustery evening in late fall. But I wanted to keep Durga company and hear what he had to say. And I was curious about the climate vigils. Other friends had found them meaningful and, knowing my interest in climate justice, had suggested that I check it out.

That evening, the vigil organizers might have been discouraged. There were only ten or so people there when things got going, about twenty all told by the end. But the space they created that night brought together Durga, sharing about the impact of climate change on Nepal on a cross-Canada speaking tour with Mennonite Central Committee, with Green Party MP Elizabeth May, a Canadian politician attending the UN’s climate summit. It’s an unlikely story of crossing paths. And it’s a story about faithfully showing up for change in small, concrete ways, of doing what is possible and knowing that the outcomes could be unexpectedly transformative.

In their handbook for organizing and movement-building, Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba draw on decades of activist work in the prison abolition movement. They advise those who want to enter into the hard and necessary work of the struggle for social change and justice to create space to practice hope and to practice grief. These concepts are not opposites; both call us to reject apathy and indifference to the state of the world. And both call us into community to experience them together in a transformative way. As Hayes and Kaba write, “We do not need to believe that everything will work out in the end. We need only decide who we are choosing to be and how we are choosing to function in relation to the outcome we desire and abide by what those decisions demand of us.”[xi]

That is a freeing thought. We don’t have to see all the way to the ending—just toward the next steps—to make a flourishing future, a livable future for people and all creation, a reality. We don’t have to do everything alone. We need only take the steps ahead of us according to the values we care about, trusting that even though not everything will work out, the steps we take—the seeds we plant—can make that livable future just a little more possible. Seeds planted in the soil of history, in grief and hope, in mutuality and interdependence as we turn toward others for care and support just as we offer ourselves in return. Seeds planted in the spirit of humility and wonder: we are an interconnected part of an unknowably vast universe with the power to influence it in our daily living.

The actions of one person alone did not get us into this mess. It will require more than individual actions to get out of it. It is increasingly clear to me that this work can only be done in community with others. It doesn’t really matter whether I feel optimistic or pessimistic, or whether I define my internal mental state as hopeful or despairing. What matters is the commitment to keep showing up with others, to believing together that it is worth striving for things to be different from how they are. To begin living together as if the future we want is here. We need the moral support of community, the feeling of belonging to something bigger, the relationships in which we find joy and companionship along the journey, people to mourn with and people to rejoice with. To make the kind of changes at the scale we need, this work needs bigger and broader coalitions of people who learn from and challenge each other to go deeper into care and possibility, weaving together the fabric of community we need to live the alternative futures we imagine into being. I am not alone; we are not alone. We do this together, embedded in the miraculous hospitality of our planetary home that sustains the only life we know to exist anywhere in the universe. Holding on to connection, relationship, and joy even in, especially in, times of suffering and grief.

Chapter 4

[i] International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development et al., Glacial Lakes and Glacial Lake Outburst Floods in Nepal (Kathmandu: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 2011), 7.

[ii] Philippus Wester, Sunita Chaudhary, Nakul Chettri, Miriam Jackson, Amina Maharjan, Santosh Nepal, and Jakob F. Steiner, eds., Water, Ice, Society, and Ecosystems in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: An Outlook (International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, 2023), vi, https://doi.org/10.53055/ICIMOD.1028.

[iii] Caroline Hickman et al., “Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey,” Lancet Planetary Health 5, no. 12 (December 2021): e863–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

[iv] Nancy Elizabeth Bedford, Who Was Jesus and What Does It Mean to Follow Him?, The Jesus Way: Small Books of Radical Faith (Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press, 2021).

[v] Galen Peters and Robert A. Riall, eds., The Earliest Hymns of the Ausbund: Some Beautiful Christian Songs Composed and Sung in the Prison at Passau, Published in 1564, Anabaptist Texts in Translation 3 (Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press; Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 2003), 21.

[vi] Peters and Riall, 83.

[vii] Robert Friedman, “Ausbund,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, January 15, 2017, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Ausbund&oldid=144754.

[viii] C. Arnold Snyder, Anabaptist History and Theology: Revised Student Edition (Kitchener: Pandora Press, 1997), 79–183.

[ix] Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone, Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re In with Unexpected Resilience and Creative Power, rev. ed. (Novato, CA: New World Library, 2022), 63.

[x] Bedford, Who Was Jesus, 71.

[xi] Kelly E. Hayes and Mariame Kaba, Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care, Abolitionist Papers (Chicago: Haymarket, 2023), 176–77.