A welcome to Penelakut Island part 2

Later that afternoon, we asked Jill and her sister Valerie if we could visit a village site that had been on the front lines of colonization. We took a tour of the island, winding up on a muddy road that took us through a band-sanctioned clearcut logging operation. Lack of employment and revenue confront First Nations constantly, and a land base that is the barest fraction of their traditional territories means that making ends meet is extremely difficult for both individuals and First Nations governments.

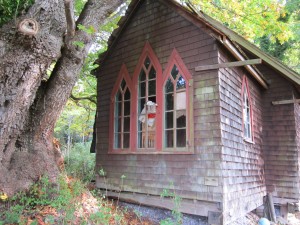

After navigating a very muddy track that Chantal dubbed a “Congolese road”, we reached the site of the former village of Hwlumelhtsu, noted on maps as Lamalchi Bay. All that remains are some Aboriginal fortifications and a heap of pure crushed shells. On that midden, a small Anglican church stands, now abandoned.

The 100 acres around it were set aside for church and non-Aboriginal use as punishment for the Penelakut people who fought the takeover of their lands. In 1863 British gunboats sent in response bombarded the village into the ground; Jill told us that warriors who had gotten hold of firearms drove the ships off. Yet the community still lost this portion of its recognised land as punishment. Now the site fronts a rare freshwater spring, beautiful bay, and perfect beach, quiet under the late afternoon sun. We found it a profoundly sad and peaceful part of Penelakut traditional territory.

id=”attachment_1305″ Chantal, Rachel, Valerie and Jill in front of the elementary school. The carvings represent traditional canoes and are part of the beams that pass through the entire building.

Our final visit was to the elementary school, a lovely building complete with a talking circle area instead of the usual everyone-look-to-the-front set up.

The space felt lively and warm even in the absence of the children. Art of many kinds graced the walls.

The children are taught the Hul’qumi’num language and go on camping trips to different parts of the territory.

id=”attachment_1309″ The children are taught basic vocabulary as soon as they start school. Over 80 years of residential schooling almost – and deliberately- erased the Hul’qumi’num language in the community.

The school is rightly a source of pride; unfortunately the older kids have to go to school off the island, relying on expensive ferry or boat rides. We left the school and looked out across the soccer field and its laughing players. In the distance and above the field stood the last remaining building from the residential school. May its legacy of violence and dispossession be slowly washed away by the efforts of women, men and children of courage like Jill–and replaced by peace, pride and justice.